The

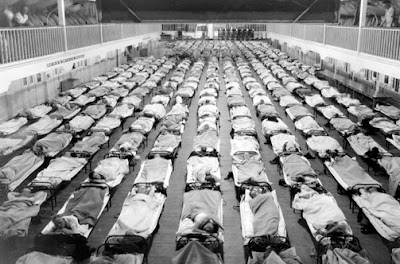

Spanish Flu Influenza Pandemic of 1918

Unlike conventional flu seasons and epidemics where the most vulnerable are often as common knowledge would suggest the very young and old due to the possession of a weak immune system, the 1918 flu victims were surprisingly those in the prime of life around the ages of 20 to 40. This sinister and ominous virus rather invoked a cytokine storm or a surge within the activity of the immune system. As the victim's defense mechanisms began to overreact, their lungs absorbed fluids and slowly built it up to the point where they could no longer breathe. They essentially drowned by their own body fluids. It was for this reason why the young and healthy in the prime of their lives were the most liable to this nefarious malady.

Unfortunately at that time, scientific knowledge was nearly devoid about viruses and so many deemed the malignant disease was induced primarily by a bacteria. The lack of the essential knowledge regarding viruses burdened the development of any vaccinations along with any formal investigations of the flu. It was not until after the discovery of viruses that serious speculation and research began on the nature of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. In order to obtain a better understanding regarding the characterization of the virus, a team of scientists voyaged to Alaska in the late 1990s. There buried under permafrost, they extracted lung tissue samples from a native Alaskan woman frozen for eight decades. Being well preserved, the lung samples which contained tangible pieces of the pernicious virus were brought back to a lab. After several years with the application of advanced laboratory techniques known as reverse genetics, the scientists involved in this research were able to successfully sequence the viral genome as well as literally reconstruct the actual flu specimen from scratch. In other words the 1918 Flu Pandemic virus has been resurrected from the grave and vigilantly kept under highly secure quarantine. In spite of ethical concerns regarding the implications of a novel approach, it is hoped that such research on the virus will culminate in the necessary knowledge to preclude another deadly pandemic from ever recurring again.

One major question that has haunted many is whether such an apocalyptic plague can ever possibly occur if not in our lifetime? While the odds are at best slim and remote, there is always the possibility that such deadly man-made specimens can be genetically engineered in laboratories as a method of bioterrorism. If there is any valuable lesson that can be obtained from the 1918 Flu Pandemic, it is that nature itself is capable of being far more unforgiving and portentous than previously thought and envisioned.